Wayne Thiebaud, Pies, Pies, Pies, 1966

Pi Day is an annual celebration of the mathematical constant π (pi), observed on March 14, since 3, 1 and 4 are the first three significant numbers of π. Established in 1988, this event involves holding pi recitation competitions or – better still – eating pie. Here I am proposing an alternative way to honor the occasion: exploring pie making in the early America before electric ovens and ready-made crusts came along. Glimpses into kitchens, recipes and profiles of pioneering celebrity chiefs set the stage for our own culinary experiments with centuries’ old recipes.

Our story starts with the nation’s first consummate host and hostess: George and Martha Custis Washington. Almost every aspect of their lives was commemorated in text and image, and their kitchen was no exception. In 1857 figure painter Eastman Johnson and landscapist Louis Mignot visited their Virginia plantation Mount Vernon to make sketches for future paintings. One product of the trip was Johnson’s Washington’s Kitchen, Mount Vernon (1864) featuring an African American woman and children seated by the hearth where thick crusted pies were laboriously prepared.

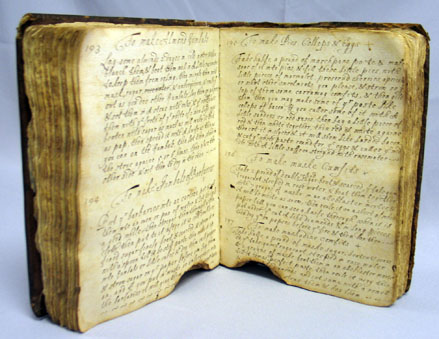

Martha Washington’s cookbook that survives in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania provides more personal insight. Such precious volumes were written for a daughter so that she could take the family recipes with her when she married and had her own home and kitchen. Martha’s mother-in-law Mrs. Custis gave it to her and she kept it handy for fifty years before bequeathing it to her granddaughter Nelly Parke Custis. The five hundred recipes have fortunately been transcribed from the original handwritten manuscript by Karen Hess in Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery and Booke of Sweetmeats (NY: Columbia University Press, 1996).

Martha Washington’s Cookbook, Historical Society Pennsylvania

By-passing desserts like mince pie, I was intrigued by the instructions for a pie made with “lettis,” referring to various leafy green vegetables including spinach, chard, and cabbage. The recipe reads:

“When you have raised ye crust, lay in all over the bottom some butter, & strow in some sugar, cinnamon, & a little boyle yr. cabbage lettis in a little water & salt, & when ye water is drayned from it, lay it in yr coffin with some dammask pruens stoned; then lay on ye top some marrow & such seasoning as you layd on ye bottom. Yn close it up and bake it.”

The combination of cabbage and prunes – strange to our taste – reflects the diverse ethnic origins of cookery in colonial America.

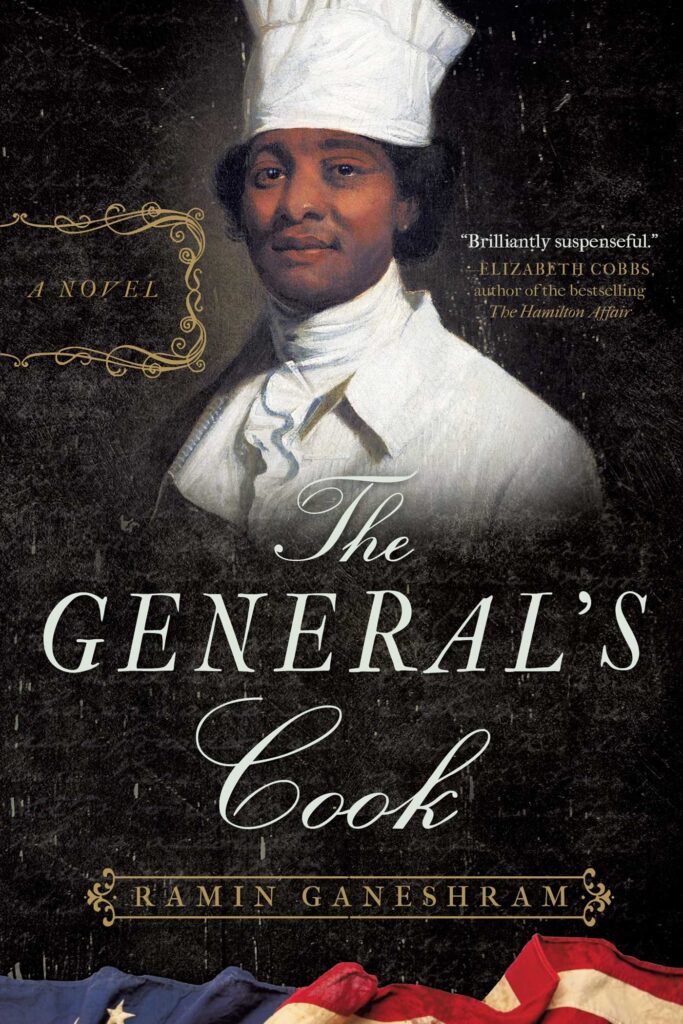

The ability of George Washington or Thomas Jefferson to set the standards for culinary excellence in the fledgling nation was due to the skills of enslaved chefs of African descent. Dishes that were celebrated at Washington’s presidential dinner parties were prepared by Hercules Posey, whose culinary skills were legendary but who was nonetheless an enslaved worker with few records to document his achievement as “America’s first celebrity chef.” Conducting research for her novel The General’s Cook, Ramin Ganeshram uncovered the testimony of Washington’s step grandson George Washington Parke Custis, who remembered him as “a culinary artiste” and “dandy” whose “underlings flew to his command” (including paid white servants). In 1797 he walked away to freedom in New York, where he worked as a cook and caterer until his death in 1812. While none of Posey’s recipes survive, period accounts detail his fabulous meals that included fruit pies. Happy Pi Day!