Katherine Manthorne (c) 2022

Telling the Lives of Visual Artists: A Female Artist in the Pioneer West

Artists don’t make it easy for their biographers. The intensely-private Winslow Homer is one example of the reluctant painter who – when he sensed a journalist was pursuing him – sequestered himself inside his studio and placed a sign on the door that read “Winslow Homer is not at home.” He insisted, like many, that his art should speak for itself, while the details of his daily existence were irrelevant. How then does the passionate biographer gather research and narrate the life of the individual who created a complex body of work at a particular historic moment? With persistence, material can be gathered and books completed, but then what? Books focusing on the careers of writers – novelists, poets and essayists – are eagerly consumed by the American readers, who can conveniently find them under the heading of “Literary Biography.” Conversely, there is no comparable rubric for the life stories of those who create images. Does this mean that the public doesn’t really care about the visual arts, or is it that their lives just don’t translate into exciting tales? How can writers make their lives more relevant and accessible?

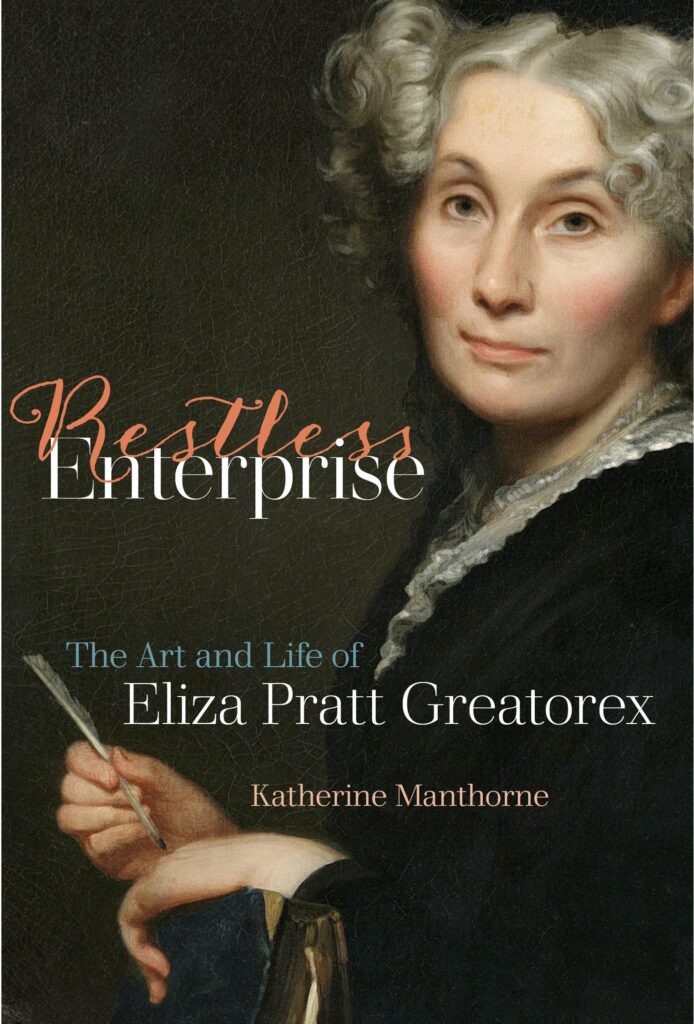

These are the questions I struggled with as I pondered Homer’s contemporary Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819-1897), the most prominent female artist in post-Civil War New York. Slowly accumulating the details of her life, I became hooked on her personal and professional story and in December 2020 – at the height of the pandemic – the University of California Press published my monograph entitled Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex (fig. 1). The book follows her successive reinventions as as landscape painter, urban graphic artist and plein-air etcher while tracing her political advocacy for Women’s Rights, architectural preservation and the place of the Irish in America. A widow with four children and limited finances, she charted her path to success in the male art establishment to become the hero of her own life’s journey. Here journey is the operative word, for her’s was a peripatetic life that is perhaps best told as a travelogue. Bearing in mind that it was taboo in her day for a woman to travel without a male escort, I want to share one of her many adventures as we celebrate her birthday December 25, 1819.

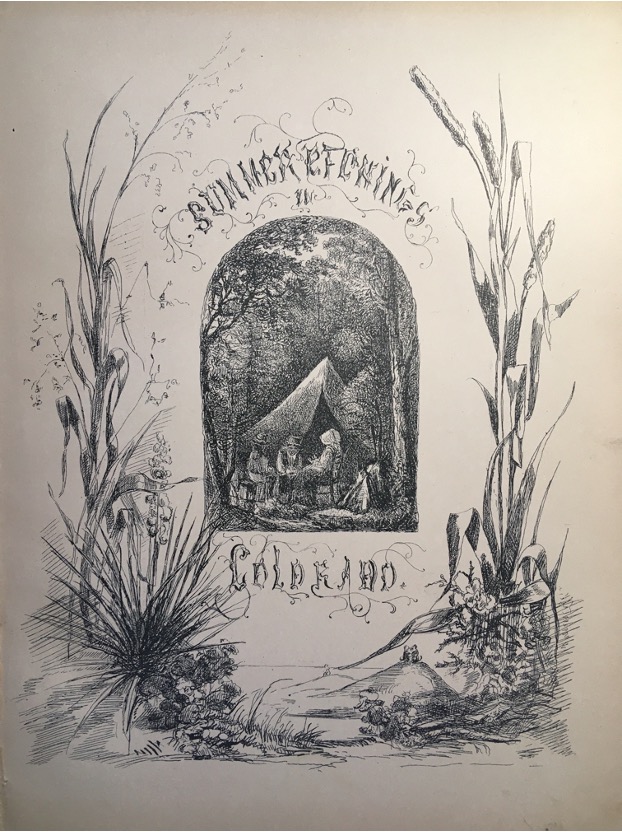

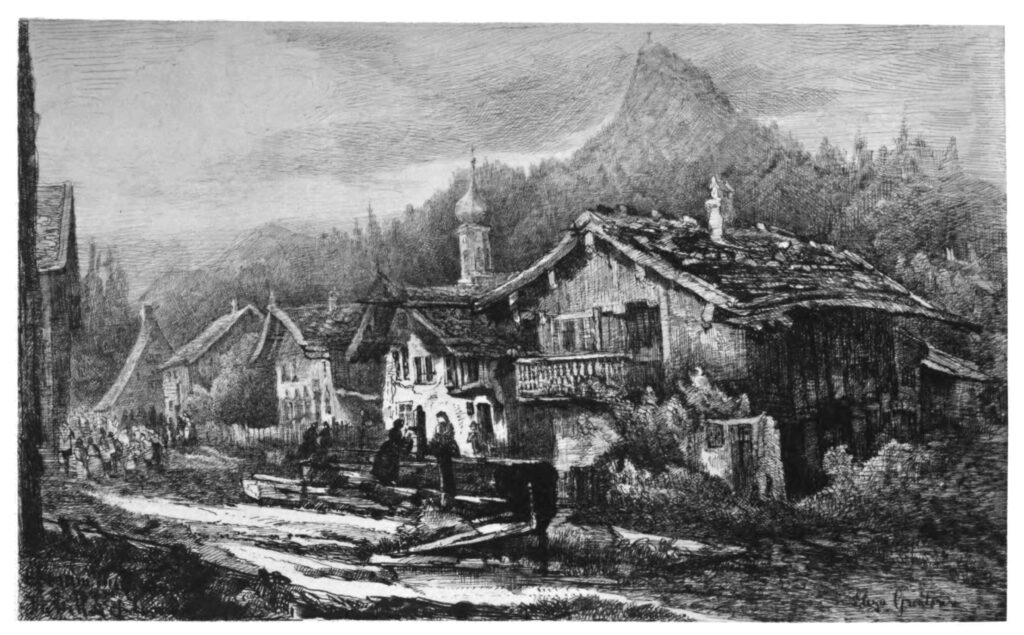

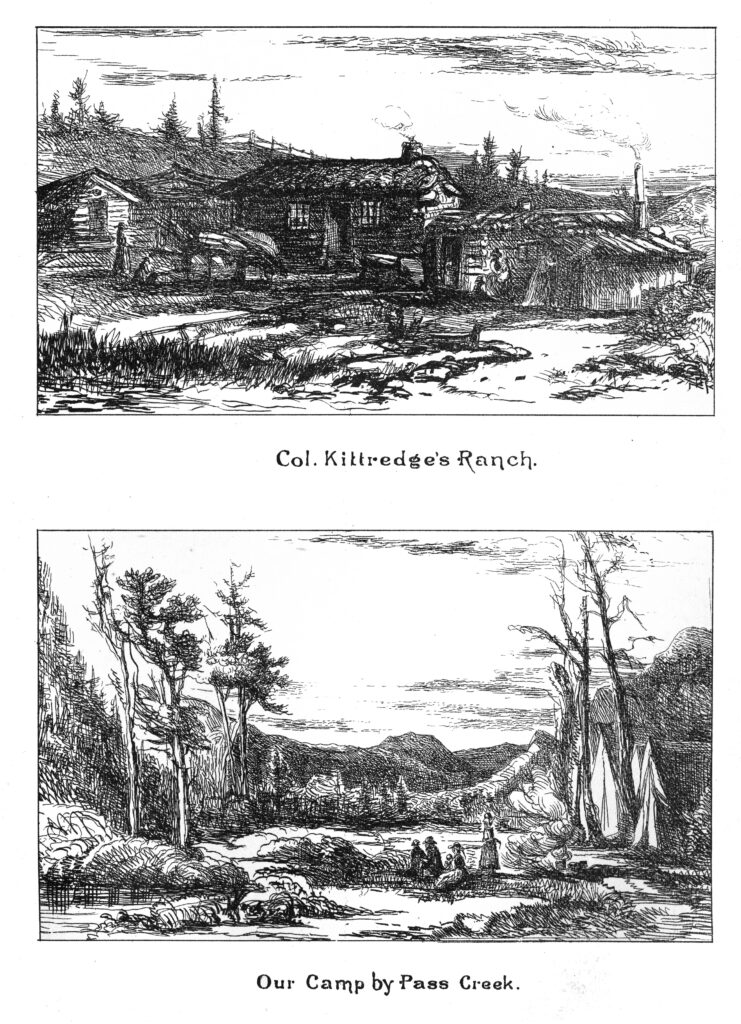

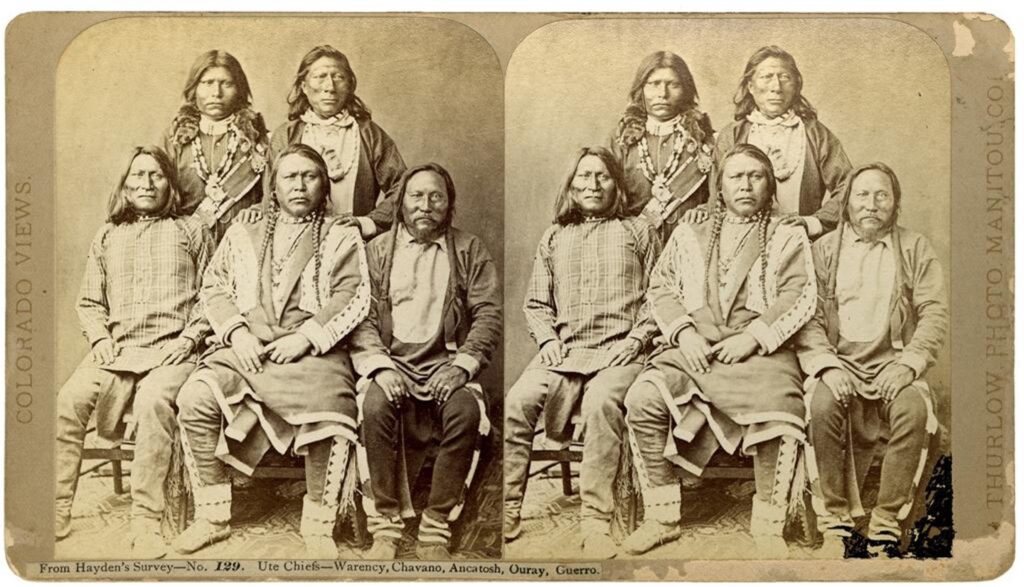

“Mrs. Greatorex, an artist of considerable note in the east … is en route to Colorado on a sketching tour” a Denver newspaper announced in July 1873. She intended “to procure illustrations for a work on this territory” which she published that December as a book Summer Etchings in Colorado, just in time for the Christmas market (fig. 2). Four years earlier the Transcontinental Railroad began conveying travelers across the US in less than a week, a vast improvement over the months of bouncing along in a saddle or the backbreaking stagecoach seats in former times. Always in search of new material for her art, Greatorex had begun planning a trip to the Rocky Mountains during her 1870-72 sojourn in Bavaria (fig. 3). She also thought that outdoor life (fig. 4) would be a good experience for her two daughters — Kathleen, age 23, and Eleanor, age 19 – both artists-in-training. So the trio headed west by train from New York to Denver, then south, to arrive at the newly founded Colorado Springs, where they encountered Chavano and other Ute Indians (fig. 5). From there they made the arduous climb up Cheyenne Cañon, celebrating their achievement by making an on-the-spot drawing and inserting the three female figures on the ledge just below the falls (fig. 6).

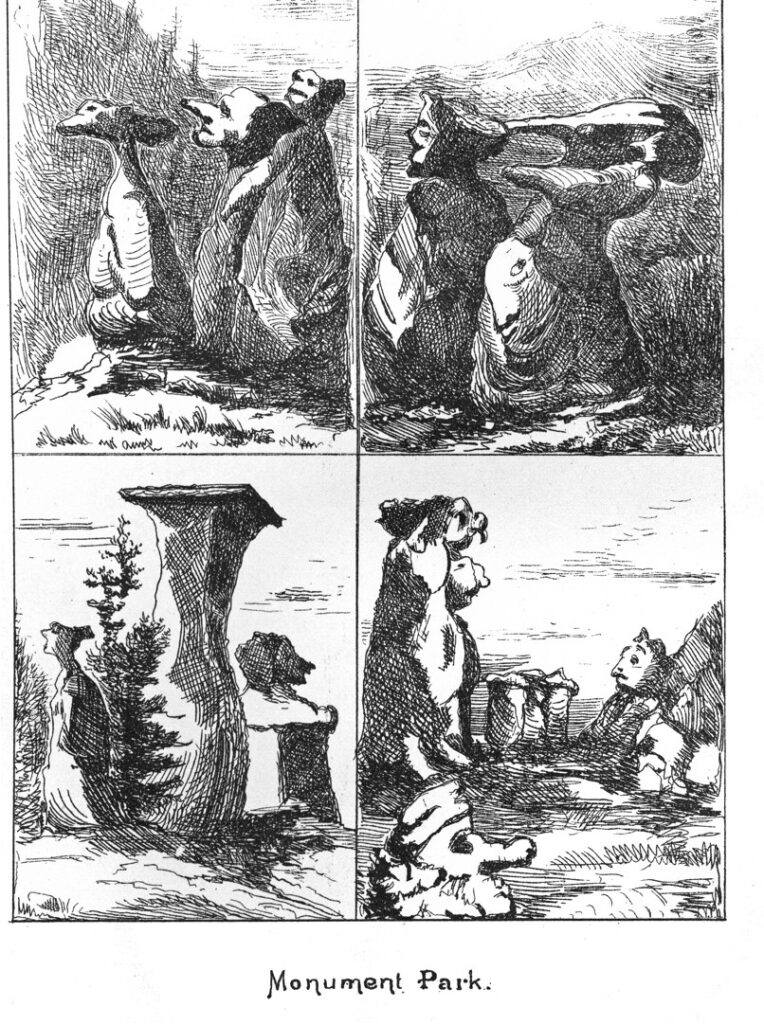

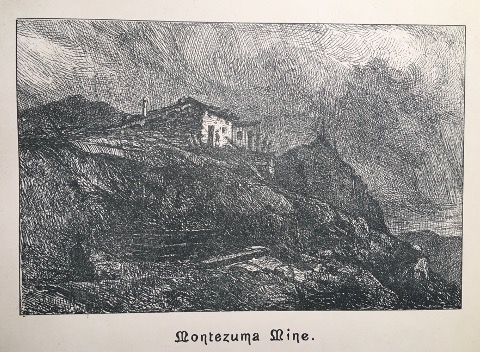

They explored the Garden of the Gods, where she rendered the fantastic rock formations (fig. 7). And they survived the perils of an ascent up Mount Lincoln and then a descent into Montezuma mine, considered the highest in North America (fig. 8). “From Pueblo to the coal mines is the wildest bit of country I had yet seen,” she wrote in her book. “We enter the mines. By the twinkling lamps carried in the miners’ hats we see & wonder at the dark processes of mining…. Later we turn away from those living tombs… and the hard lives passed in the Pueblo Coal Mines.” Her pictures convey the Rockies from a woman’s perspective while her Colorado story possesses all the elements we identify as characteristic of western sagas: enterprise, talent, hope, tragedy, and sheer love of adventure. Telling the life of this pioneering female visual artist was itself an adventure.

Happy Birthday, Eliza Greatorex!!