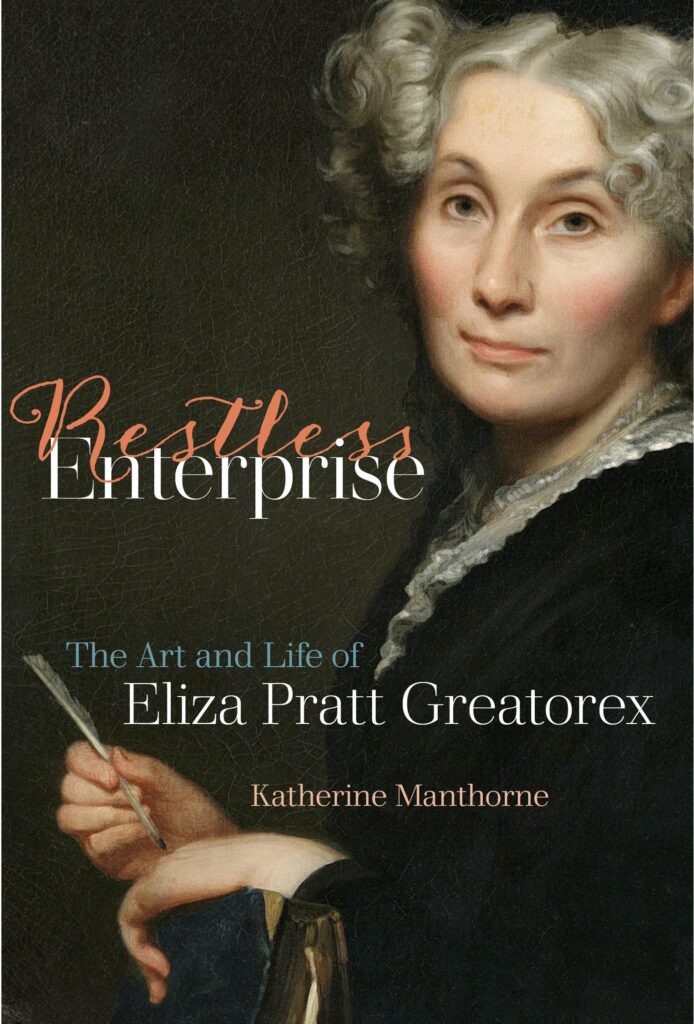

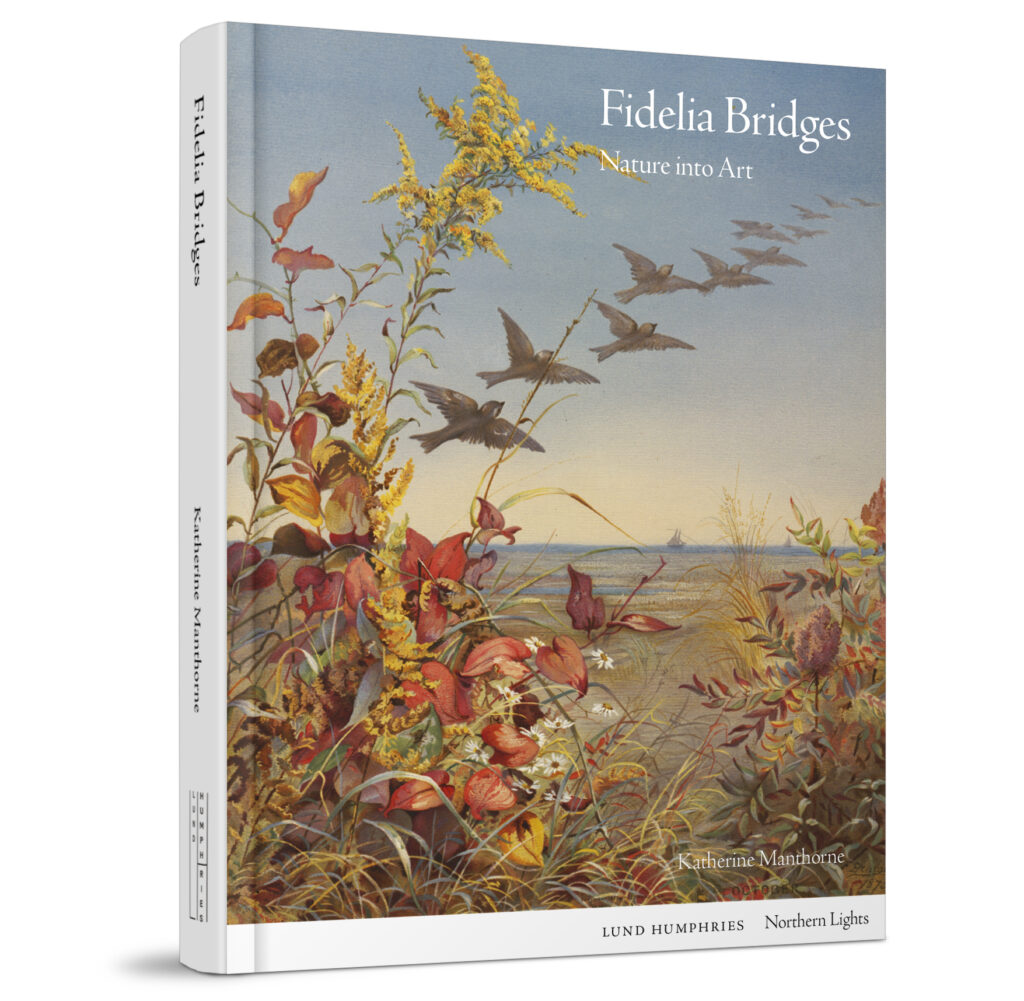

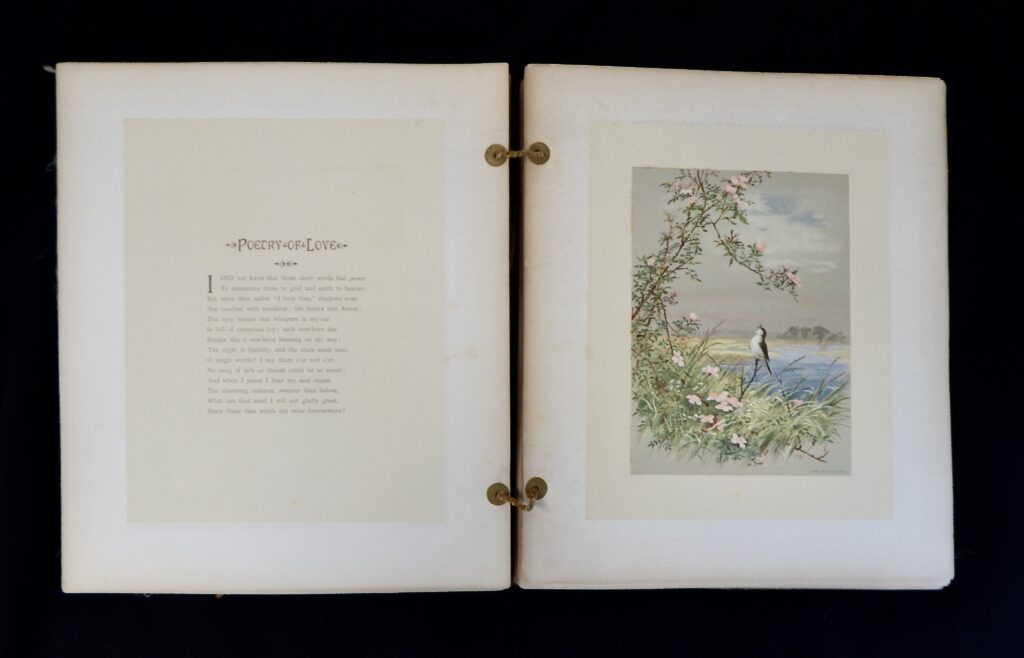

Conducting research for my new book Fidelia Bridges: Nature into Art (London: Lund Humphries, 2023; fig. 1) a document emerged among her papers that stopped me in my tracks: a 2-page handwritten poem with illustrations in the margins that bore the final line “Valentine Feb. 14, 1891,” all done in brown ink. Bridge created a two-track body of work. She made fine art paintings primarily of birds and wildflowers that she exhibited in prestigious venues around the United States and in Britain. Simultaneously her imagery was reproduced as chromolithographs for the popular market. Her commercial work was published by Louis Prang as greeting cards and gift books for Christmas, Easter and yes- you guessed it – Valentine’s Day (fig. 2). It was intriguing to think of someone creating a greeting card for her, but who?

I began obsessing over the possibility that I had finally found a juicy tidbit related to some love interest – male or female – to spice up her life story. Samples of handwriting were compared, the content scrutinized for any revealing clues, and the document shared with a friend who was familiar with the artist and her circle.

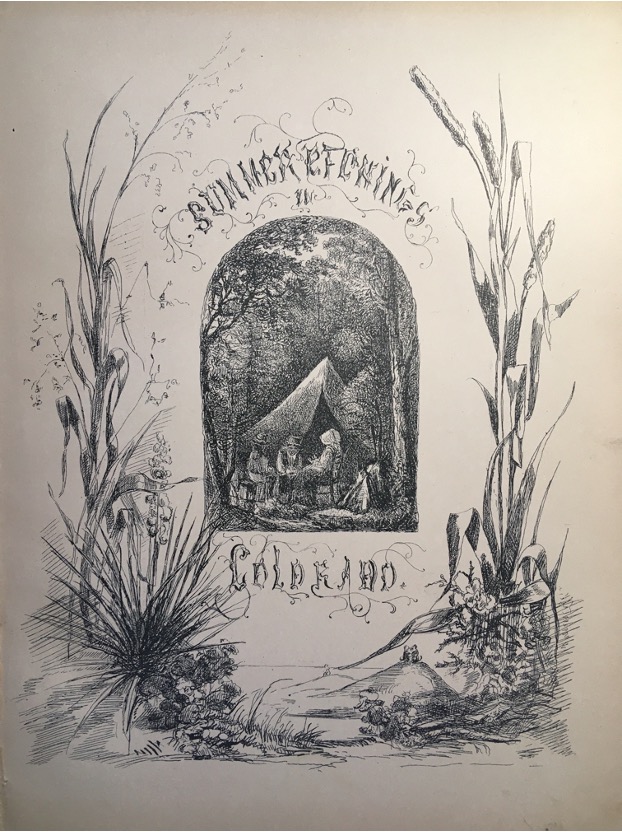

Who were the likely suspects among her male friends? Her close confidante, artist Oliver Ingraham Lay, came to mind but was immediately eliminated as he had passed away in 1890 (fig. 3). William Trost Richards was a life-long friend, but this did not seem to be his style. Was there another male figure yet to emerge from the archives? I couldn’t rule out women, like the sculptor Ann Whitney, with whom she shared a close camaraderie. Then there was Annie Brown, one of her charges when she was a governess who became a life-long friend. All this personal speculation seemed to be to no avail, the answer had to be concealed in the text,

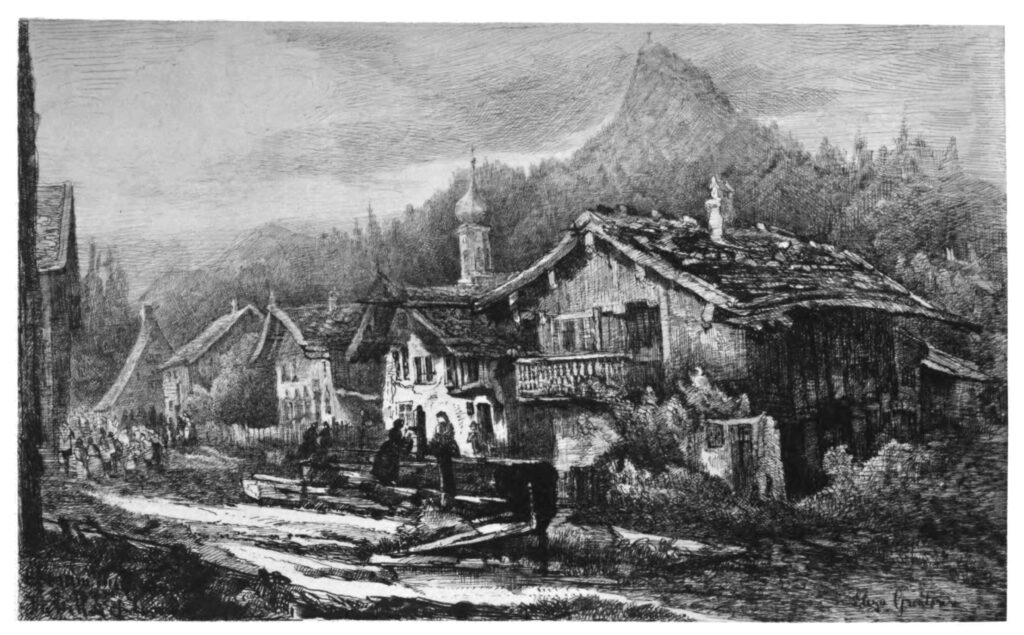

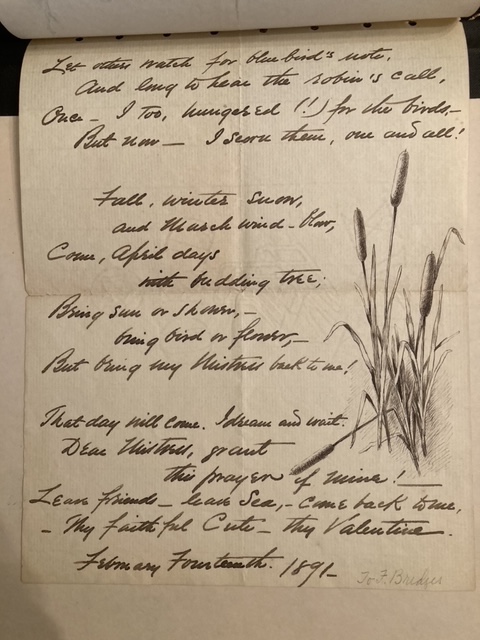

The lines on the second page (fig. 4) referenced her watercolors of New England birds she depicted over the four seasons of the year:

“Let others watch for blue birds note,

And long to hear the robin’s call,

Once- I too, hungered (!) for the birds,-

But now – I scorn them, one and all!

Fall, winter snow

And march wind blow,

Come, April days

With budding tree;

Bring sun or shower –

Bring bird or flower, –

But bring my mistress back to me!

That day will come. I dream and wait

Dear Mistress, grant

This prayer of mine!-

Leave friends – leave Sea- come back to me

Thy faithful Cute – thy Valentine.

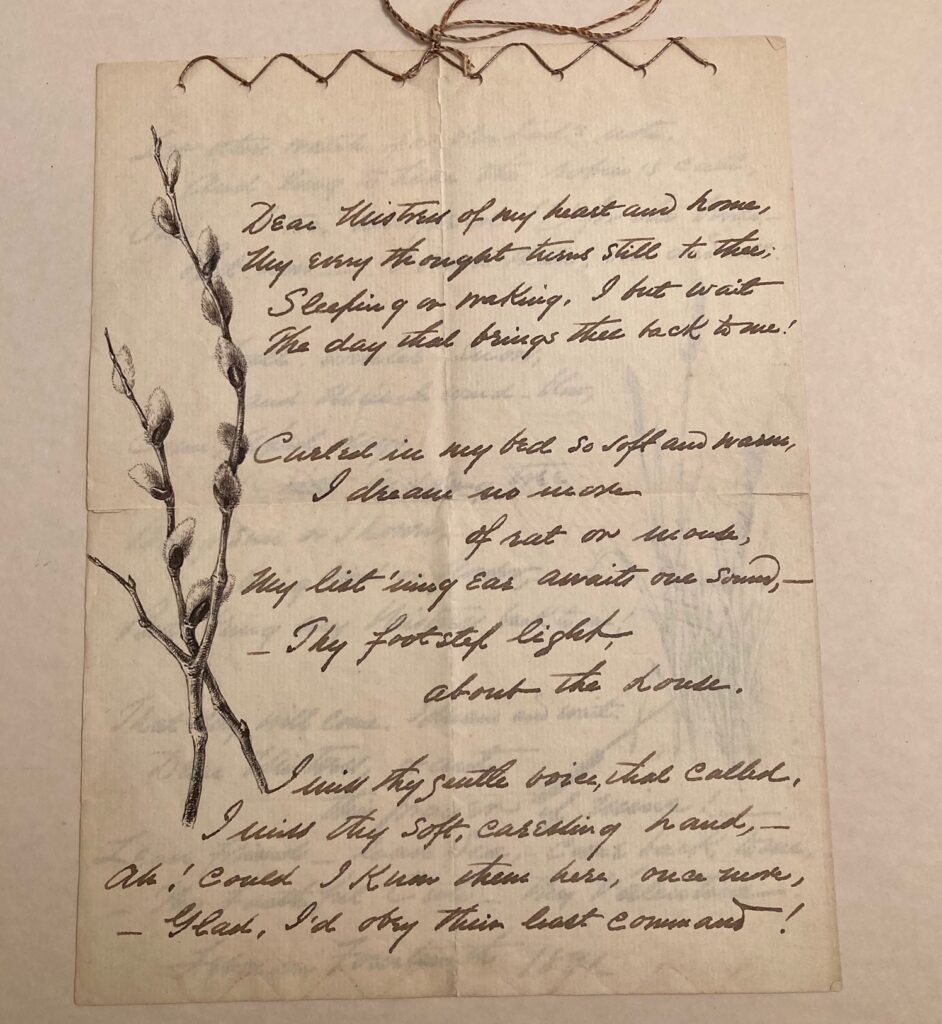

But that seemed to lead nowhere, so I went back to the first page (fig. 5):

“Dear Mistress of my heart and home

My every thought turns still to thee

Sleeping or waking, I but wait

The day that brings thee back to me!

Curled up in my bed so soft and warm

I dream no more

Of rat or mouse

My list’ening ear awaits one sound,-

They footsteps light,

About the house.

I miss thy gentle voice, that called

I miss they soft, caressing hand,-

Ah! Could I know them here, once more,

Glad, I’d obey their last command!”

The illustrations provided some help in my decoding efforts: page one was adorned with the branches of a pussy willow and page two featured cattails.

Any guesses?

Then it hit me, Fidelia had been a cat lover all her adult life and was photographed and even painted with her feline friends. The line that reads “I dream no more of rat or mouse” gave it away. Someone had crafted the message from the point of view of her cat!

So even though I have yet to crack the riddle of who penned these lines, it was meant as a kindly joke and was not evidence of a hot romance after all.

HAPPY VALENTINE’S DAY!

Order your copy. CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW